A White-Collar Crime, A Blue Collar Lie: The Story of James Bingham

By Shala Scarlato

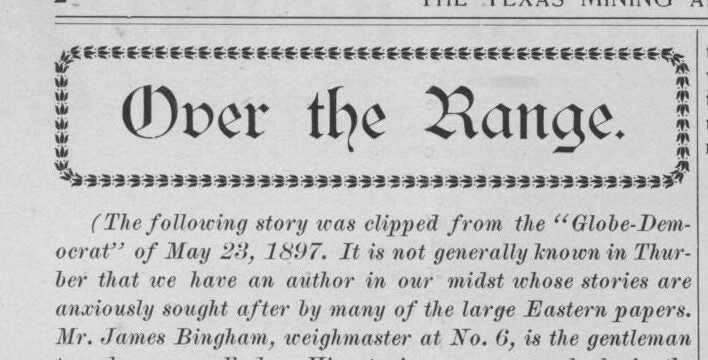

James Rollins Bingham was a hardworking, published author that found a life in Thurber, Texas. The weigh master of the No. 6 mine found a place to stay with the Yie family who ran a small boarding house. He started in Thurber as a rock breaker but worked his way up to weigh master, then eventually bookkeeper. He was a published author, finding his work published in papers across the United States. James Bingham was a bit reclusive, no one really knew his history, and for good reason. James Bingham had a secret.

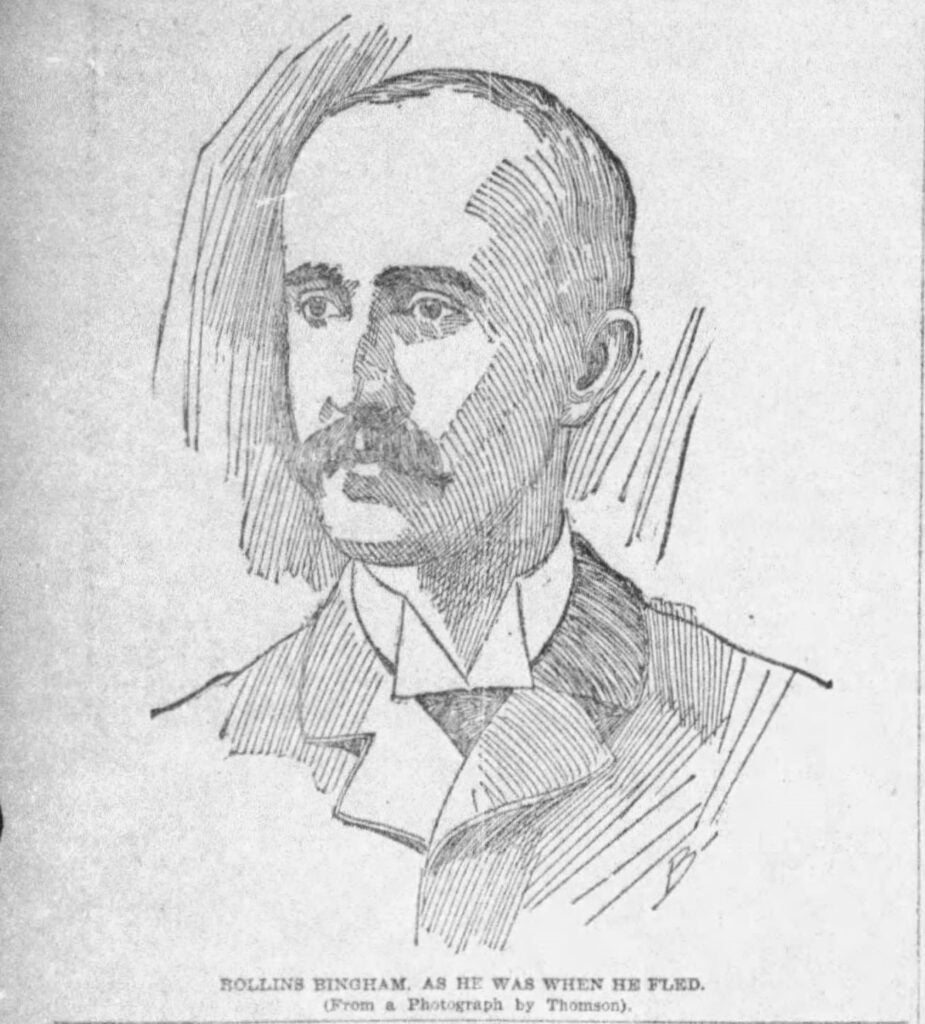

James Rollins Bingham formerly known as Rollins Bingham, was born in September of 1861 in Missouri to General George Caleb Bingham and his second wife Eliza Thomas. He was the only child of the couple. General Bingham was Missouri’s Adjutant General, and a painter known for his paintings of frontier life. Rollins Bingham grew up wanting for nothing, but that wasn’t enough for him. General Bingham died on July 7th, 1879, leaving behind his third wife Martha A. Lykins. Rollins was told by his father to take care of his stepmother, and she continued to live with him for a time.

What Rollins did next shocked everyone, he forged deeds of property left by his father to his stepmother. He took out liens in his stepmother’s name against properties now hers by stealing the legal stamps of his law practice partners. The total amount of his theft resides between $20,000 and $25,000 dollars, today equaling over half a million dollars. Luckily for Rollins’ stepmother, she discovered his actions before her death, and disinherited him and his sister Clara. The money that remained she left to her niece and nephew. Leaving only a few paintings to Rollins and Clara, but due to Rollins’ theft they were liquidated to pay back the liens, leaving him penniless. Then he went into hiding for twelve years. While a few friends knew where he resided, they refused to give up his location.

Rollins found his way to Thurber, likely by way of his sister and brother-in-law who lived in Stephenville. He stopped going by Rollins and became known as James Bingham. James became known in the community for being quiet but well liked. He stayed in the same boarding house as W. K. Gordon. Many boarders lived in the Yie household, allowing for friendships and business relationships to blossom. Many of these names were printed alongside Bingham’s when the newspaper reported on local social events. Bingham was a writer before he came to Thurber, and he didn’t stop writing while there. Many people were unaware of his artistic talents until his work began being published in the “Texas Mining and Trade Journal” for others to read.

James’s nephew is listed as visiting often enough that it is possible he found a residence among Thurber for a short time. The “Texas Mining and Trade Journal” also featured ads for James’ brother-in-laws’ and nephews’ real estate business. Unfortunately, James’s sister passed away in 1900, and James’ health saw a rapid decline. Due to this James had to move into a hospital in Fort Worth. After spending six months in the hospital, James Bingham picked up his full name again and wrote to the judge of Kansas City, Missouri and the prosecuting attorney, “I have worked hard and honestly, but of recent years my health has not been good, and I have been able to save nothing. What I desire is to come back to Kansas City, plead guilty and take my punishment.” James Rollins Bingham then surrendered himself to the Dallas Police Department.

Whether it was Bingham’s sad state, slick tongue or the kindness of others, he walked from his trial a free man. No one brought forth a case against him. With his stepmother long gone, and the liens covered, he continued his life as a free man. He worked as a writer for the Kansas City Star until his death from pneumonia in 1910.