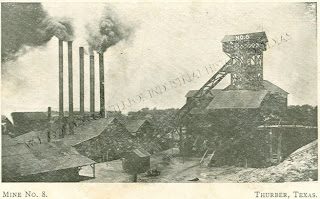

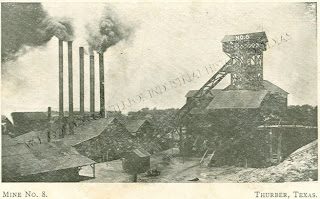

Battling the Blaze at Mine #8

By David Buster

At approximately 2:30 am June 3 1904, the night engineer in the tower building of No. 8 Mine discovered a fire. Company investigations revealed that the conflagration most likely began when men from the machine shop making repairs, dropped cigarette butts or some other flammable material into one of the dust bins. This one careless act would have devastating consequences.

Immediately, an alarm rang out to alert the citizens of Thurber and a party of volunteers formed to combat the blaze. The volunteers struggled in vain as the fire spread from bins throughout the woodwork of the mine. The flames engulfed the mine tipple, the majority of the wooden mine shaft structure, and the timbers underground. Because the fire grew so rapidly, a conical-shaped collapse occurred at the base of the mine. The subterranean loading entries filled with smoke and the temperature soared.

After several trips underground, volunteers rescued the fan house and secured multiple entrances to the mine. The men battled life-threatening conditions caused by the growing amounts of smoke, heat, and water inside the mine shaft. Several days later workers determined it vital to close the shaft openings to suffocate the persistent blaze, which was still burning throughout the mine pillars and large fall (collapse) at the bottom.

Fifteen days later when the workers attempted to re-enter the mine, the fire revived and dispersed in all directions. The miners knew they would have to conduct a hands-on fight to contain it. Workers created a new air shaft that allowed men to crawl on their stomachs towards the bottom of the main shaft. The only way for them to breathe was to keep their heads close to the mine floor. Once there, they ran a water hose from the surface through the airshaft to combat the blaze with heat and smoke suspended mere inches above them.

The miners battled the fire using this method until they arrived at the powder house situated at the south side of the main shaft. The almost thirty kegs of blasting powder stored there held the potential to cause a large explosion which would destroy one of the company’s most productive mines. Workers doused the superheated room then immersed the kegs themselves in water to prevent greater destruction.

At last, the miners extinguished the flames lingering at both the north and west openings which were under constant threat of a cave-in and put an end to the persistent inferno once and for all. The cost of the fire was immense. Texas and Pacific Coal Company reported that the fire caused $21,701.21 in losses of mining equipment and buildings. Thanks to the firefighters’ success, the mine was repaired and production resumed. For their brave efforts in battling the blaze, the company paid volunteers maximum wages and rewarded them with a “handsome suits of clothes.”

Sadly, two employees, Eli Thomas and H.M. Long, were crushed by falling timbers weakened by the disaster. The number injured is unknown. Mining today is arguably as dangerous as it was almost 106 years ago in Thurber. Even with current advancements in technology and safety procedures, mining continues to be perilous as evidenced by the recent explosions in the coal mines of West Virginia that killed twenty-nine miners.