Was the Brother of the Company President Poisoned?

By Lindsey Light

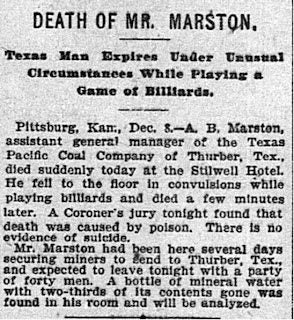

In December of 1902, A. B. “Bert” Marston arrived at the Stilwell Hotel in Pittsburg, Kansas, to gather African American workers to go with him to Thurber, Texas, to mine coal. Marston was the assistant storekeeper of the Texas Pacific Mercantile and Manufacturing Company (TPM&M). TPM&M was a subsidiary of the Texas and Pacific Coal Company led by President Edgar L. Marston, A. B. Marston’s older brother.

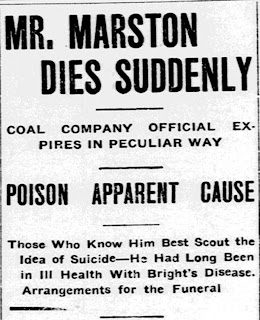

On December 8, while playing billiards at the hotel, Marston fell to the floor with convulsions. Though men carried him to his room and a doctor arrived quickly, nothing could be done. He began to vomit and froth at the mouth and then died. Soon after, a panel of doctors started investigating the cause of death. In Marston’s room there was a bottle of mineral water found with a small amount of liquid left in it and business paper work. There were no signs of suicide.

The panel of investigators retained statements from the people who last had contact with Marston. Richard Hayden, a black man, accompanied Marston on the trip specifically to recruit black men from surrounding coal camps. Hayden told the panel that Marston purchased a bottle of Manitou mineral water like the one found in the hotel room, in South McAlester, Oklahoma, which was at the time Indian Territory. Unfortunately, there was no way to prove that the bottles were in fact one in the same since that brand was also available in Pittsburg. Also, the panel talked to A.L. Scott, a local lumberman, who chatted with Marston the night before he died. He reported that Marston knew that many people opposed him bringing in outside workers. Considering the eye-witness accounts and his symptoms, Coroner Boaz came to the conclusion that Marston died from deliberate poisoning.

Because the panel of doctors suspected that arsenic caused Marston’s death, they conducted a post-mortem examination. All of Marston’s main organs appeared to be in a healthy condition, but his stomach indicated the presence of arsenic. They sent samples to a lab in Kansas City, Missouri to test for toxins in his system. When the contents of Marston’s stomach were tested, however, no evidence of poison was found. The investigation ended at this point and no one was accused of murder. His remains were taken to Greenville, Illinois, to be buried at Montrose Cemetery.

The death of A. B. Marston remains mysterious. Though the final coroner’s report indicated he died from natural causes, no immediate illness was ever identified. Later Thurber historians failed to record the event altogether, in spite of the fact it was sensationalized in newspapers across the nation. Certainly there were persons who were uncomfortable because he was bringing outsiders to work in Thurber, but were they capable of getting away with murder? Ultimately, the circumstances surrounding Marston’s death were suspicious, but the remaining questions about what A. B. Marston succumbed to that day in Pittsburg may never be answered.